Credit: Tom Mason

South West Wildcat Project FAQs

South West Wildcat Project

After an absence of more than 100 years, critically endangered wildcats could return to the South West. Devon Wildlife Trust and partners are investigating the feasibility of achieving this. Find out more:

About the European Wildcats

What is a wildcat?

The European wildcat (Felis silvestris) to give its full name, is Britain’s only remaining wild native cat. Usually referred to as wildcat it was also once known as woodcat in England, reflecting its association with woodland habitats.

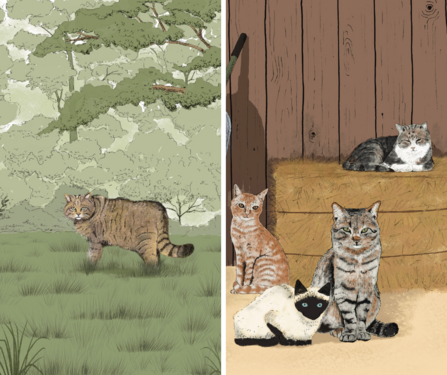

It is a separate species to domestic cats (Felis catus) which are descended from African wildcat (Felis lybica). Domestic cats may be referred to as feral cats where they are living with little or no human support, but they are not well adapted to living wild unlike wildcats who will not become domesticated. Although domestic cats and European wildcats share a common ancestor this was over 4 million years ago!

How big is a wildcat?

They are a small cat. Generally, they will not be much bigger than a domestic cat though can be up to 25% larger. They are stockier with longer legs. They tend to not prey on anything larger than a rabbit.

Illustration of a wildcat in comparison to a medium sized dog and a human of average height. Credit: @liz.scott.art

When did wildcats go extinct in South West England?

Once widespread across Britain, by the 1870s wildcats had largely been lost from England and Wales due to hunting. But a small population clung on in remote areas of Scotland which is why the European Wildcat is often referred to as the Scottish wildcat.

Why were wildcats lost from England?

Wildcats underwent rapid declines through the 19th and early 20th centuries. They were hunted as they were thought to compete for species which humans ate or killed for sport – for example rabbits and game birds. This combined with the loss and fragmentation of wooded habitats, which reached an all-time low in the late 1800’s, spelled the end for wildcats. Today they cling on in parts of northern Scotland, where the remaining wildcats are subject to critical conservation action.

What is happening to save wildcats in Scotland?

Saving Wildcats is a project dedicated to saving wildcats in Scotland. It has been recognised that the remaining Scottish wildcat population needs urgent help to avoid extinction. Since 2023, over 40 captive bred wildcats have been released in the Cairngorms Connect landscape. Further releases are planned, and animals are being carefully monitored. Survival of released animals has been very high and there has been confirmed breeding; these are all positive signs. However, there has also been challenges with a small number of wildcats being attracted to game pens and poultry. The project team and NatureScot are actively working with those affected to ensure solutions are found.

If they are in Scotland, why do they need to be reintroduced to South West England?

Unfortunately, Scotland's wildcat population is critically endangered. With low numbers and fragmented populations, they have struggled to find other wildcats to breed with. Where once it was persecution and habitat loss, today the main threat comes from 'genetic extinction' caused by interbreeding with domestic or feral cats. Although wildcats are a separate species they can breed with domestic cats and produce fertile young (hybrids). This has resulted in the Scottish population consisting of mainly hybrids.

The long-term solution to avoid the extinction of the species is to ensure new populations are reintroduced, and in time connected once again.

What do wildcats eat?

Wildcats are predominantly small mammal hunters. Their diet is dominated by rabbits where present, and rodents, such as rats, voles and mice. A much less significant portion of their prey includes birds, amphibians, reptiles and insects.

Do wildcats predate rare wildlife?

Wildcat co-evolved alongside native prey species who have developed survival strategies to deal with native predators. Wildcats mainly prey on small mammals, with diet analysis identifying rabbits as favoured prey followed by rodents. Their foraging behaviour will adjust according to prey availability, therefore if rabbits are scarce they will take more rodents. Birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects make up a smaller part of their diet. They hunt mainly by sight and sound and spend a lot of time waiting to pounce. Although they can climb it is not usually for hunting, rather seeking safety.

Birds that forage on the ground or low down (such as wood pigeon, blackbirds, pheasants) may be vulnerable, but ground nesting birds are not specifically targeted. As wildcat are reliant on widespread and locally abundant prey, this means they are unlikely to have any impact on rare species which are struggling usually because of problems such as habitat loss or inappropriate habitat management rather than predation.

An assessment of any potential conflicts with other species undertaken as part of the feasibility did not highlight any significant concerns. However, it did suggest there was little threat to bats or dormouse as these are absent or rarely recorded in the diet of populations studied across Europe. In contrast grey squirrels are likely to be predated by wildcats as they forage on the ground. As a non-native species that is impacting woodland habitats and is a known predator of nesting birds this could have a positive impact.

Where do wildcats live?

Alongside broadleaved and mixed woodland habitats, wildcats require more open habitats that support high numbers of their favourite small mammal prey. Woods are important for providing cover and den sites while low intensity grasslands and scrub habitat mosaics create great hunting habitat. Wildcats do best in complex mixed landscapes that can include low intensity farmland. They avoid people and human habitation. They live at very low densities and are dependent on prey availability.

@liz.scott.art

How are wildcats different to domestic cats?

Wildcats are a distinct species from domestic cats or feral cats. Their ecological function is quite different, they live solitary lives at low densities, and they have evolved to live alongside local wildlife. In contrast, domestic cats have wider diet and habitat niches and their relationship with humans has supported them to live at high densities where their impact on local wildlife can be a concern.

The threat of hybridisation between these two species needs to be explored carefully and mitigated against. Responsible cat ownership, such as neutering, can contribute positively to wildcat conservation.

@liz.scott.art

Are wildcats a threat to livestock, game, pets and poultry?

There's no evidence that wildcats pose any threat to sheep or cattle. Wildcats may take chickens, ducks, game birds and rabbits. However, poultry, gamebirds and pets protected from predators, such as foxes and badgers, will also be protected against wildcats. No special deterrent is required.

Do wildcats attack people?

No. Wildcats avoid contact with people whenever they can. They are shy and elusive creatures, mostly active by night. You'll be very lucky to see one, even if you live close to one of the release sites.

About the South West Wildcat project

Why is DWT considering reintroducing wildcats to South West England?

The wildcat has the unenviable distinction of being the UK's rarest and most threatened mammal. It has been recognised that to secure a future for the species, conservation action is needed to maintain the existing Scottish population but to also explore if further populations can be established within its former UK range. With no chance of natural population expansion, reintroduction is the only way this can be done.

In 2019, a preliminary assessment of the biological feasibility of reintroducing wildcats to England and Wales by the Vincent Wildlife Trust and Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, identified parts of Wales and the South West of England as the most suitable places to investigate further.

DWT along with its partners, have explored in detail if a wildcat reintroduction is possible in South West England. Any reintroduction of wildcats to Devon will be part of a National Strategy to save the species and will be undertaken following the IUCN guidelines for reintroductions. It is important wildcat projects across the UK work together to save the species.

Won't reintroduced wildcats just suffer the same fate as those which went extinct in the 1800s?

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, wildcats underwent huge population declines. This was due to loss and fragmentation of woodland habitats, combined with hunting and predator control. Woodland cover is currently back to similar levels as in the 11th century, and although in the South West cover may be lower than some parts of England, there is good connectivity via the extensive network of dense hedges. In addition, the mixed landscape so typical of the South West contains many habitats favoured by wildcat, for example rough pasture and extensive riparian habitats along steep combes and valleys.

Attitudes to wildlife and its protection have also changed in the last 150 years. There is growing support for lost species returning to our countryside, and legislation means wildcats are now a protected species. Despite these positives, species reintroductions are complex and there are many factors which need to be considered to ensure success. The feasibility work has concluded that Devon's countryside could support wildcats.

Why is DWT reintroducing lost species?

We've led or been part of many species reintroduction and recovery projects including southern damselflies, freshwater pearl mussels and narrow-headed ants. DWT's work has seen us planting thousands of trees lost to ash dieback and bringing back wildflowers to thousands of hectares of grasslands and meadows. However, its often the return of species such as beavers, pine martens and wildcats which grab the media's attention!

The 2023 State of Nature report revealed that one in six species studied in the UK is under threat of extinction. We dedicate the vast majority of our resources to ensure these threatened species and the habitats they rely on have a brighter future. However, we know our ecosystems are suffering and are out of balance – and the return of recently lost species will help nature’s revival.

It's no longer enough to try and cling on to the wildlife populations we have left - we need to bring back species too.

Why focus on re-introducing a predator when other wildlife is struggling?

Wildcats are Britain’s rarest mammal and is a species on the verge of extinction – they are part of our struggling wildlife! Wildcats evolved alongside other native British wildlife including their prey and they should be part of our ecosystem. Wildcats eat fresh meat (may take fresh carrion if times are tough) and do not supplement their diet with non-meat food. They are reliant on widespread and locally common prey and live at very low densities (3-5 wildcats per 10km2). With predator numbers limited by the amount of prey available, as a true carnivore this will be particularly relevant to wildcats.

Current understanding suggests the impact of wildcat on South West wildlife will be minimal, but it is recognised that there may be local impacts. Careful monitoring and mitigations may be needed. This will be explored if a reintroduction is developed.

Where and when could wildcats be reintroduced?

The feasibility project has identified that Devon contains suitable wildcat habitat. Wildcats prefer landscapes with a mosaic of broadleaved woodland, rough grassland and scrub. This mix can support high numbers of voles, rabbits and mice to hunt, and lots of places in which to make their dens (dens are usually found in tree hollows, under tree roots, or in old holes made by badgers, foxes or rabbits). Work is needed to identify areas where the local community would support a wildcat reintroduction.

If a reintroduction programme is developed, the first releases will not be before 2027.

How many wildcats would be reintroduced?

A reintroduction needs to establish a population of 40-50 animals. Wildcats are mainly solitary animals, are territorial and live at low densities. This would potentially mean reintroducing the cats at several sites dispersed across the best locations. A robust release strategy will need to be developed before any releases can take place. The experience gained by the Saving Wildcats project will be invaluable in designing this.

Where will the wildcats for release come from?

A wildcat captive breeding programme is established across Britain with the studbook managed by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. These are wildcats which are of native wildcat descent. Cats will be selected from this cohort which will be brought to dedicated breeding enclosures – it will be their offspring that may be released if a reintroduction goes ahead. It has been identified that including animals from continental collections could help improve genetic diversity and this is being considered.

Will reintroduced wildcats breed with domestic cats?

Despite being different species, wildcats can breed with domestic cats and produce fertile young. Interbreeding between hybrids and backcrossing with parent types produce what is known as a hybrid swarm – this results in loss of parent characteristics and genetics. This is a serious problem which has resulted in wildcats in Scotland becoming functionally extinct.

However, hybridisation does not appear to be inevitable with some populations across Europe maintaining their genetic integrity. Addressing factors that can increase the chances of interbreeding such as high numbers of unneutered domestic cats, low wildcat density and habitat fragmentation can help maintain wildcats. Perhaps the best way of preventing hybridisation is ensuring wildcats have plenty of wildcats to breed with.

If hybridisation with domestic cats can occur, how is it possible to reintroduce wildcats to England?

Evidence from wildcats across Europe reveals that you can have thriving wildcat populations in proximity to domestic cats. Hybridisation becomes an issue when wildcats cannot easily find wildcat mates because of low numbers and fragmented populations, which may be linked to poor habitat quality or persecution.

Any reintroduction will need to take this threat seriously. A key aim will be to minimise contact with fertile domestic cats as well as ensuring enough wildcats are released in suitable habitat. Preliminary surveys to investigate numbers of domestic cats in potential wildcat habitat in Devon are encouraging. Cat welfare charities already promote responsible cat ownership that includes neutering and runs Trap, Vaccinate, Neuter and Release programmes for feral cats. Understanding the work already taking place and building on this if needed within key areas will be necessary as part of a planned reintroduction.

Will feral cats be controlled as part of a reintroduction project?

The situation with feral cats is complex and is a potentially emotive subject. The project will work through existing protocols operated by cat welfare charities. The main objective of this work will be to reduce the chances of wildcats coming into contact with fertile or sick cats. There are no plans to euthanise feral cats as part of a reintroduction programme.

Would wildcats be protected after they were reintroduced?

Wildcats are protected in the UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981. They would be protected by the same wildlife laws which protect many of our other native animals. Among a range of legal protections, this would mean it will be a crime to 'deliberately or recklessly... capture, injure, kill or harass a wildcat... disturb a wildcat while it is rearing, or otherwise caring for, its young... disturb a wildcat in a manner or in circumstances likely to significantly affect the local distribution or abundance of the species'. After any release of wildcats, the project would continue to monitor the progress and welfare of the animals.

What are the next steps in the South West Wildcat Project?

Our intensive analysis of ecological and social aspects has indicated that a wildcat reintroduction is a feasible prospect, however there are more steps that need to be taken before a decision is taken to release animals. Next steps include:

- Identifying suitable release areas and investigate prey availability.

- Create a mechanism to collect and address public/stakeholder feedback.

- Development of a domestic cat management strategy within release area through consultation with animal welfare organisations.

- Development of a co-existence plan to help people adjust to living alongside wildcats – through stakeholder and community co-design.

- Ensuring a suitable source population is available.

- Develop a robust release strategy.

Reintroductions are a delicate process. The welfare of the animals is vital, as are the views of communities where reintroduction is proposed. However, one day wildcats could be a flagship species for woodland wildlife, and once again roam South West England and inspire future generations to act for nature.

Do wildcat pose a disease risk to livestock, humans, pets or wildlife?

As part of the feasibility, an independent Disease Risk Assessment was commissioned. This has identified diseases and hazards that could impact wildcats, wildlife, livestock/pets and human health. This will underpin any release programme and has clearly outlined how risks identified can be mitigated.

Promotion of responsible cat ownership, to include vaccination of key cat diseases that could impact wildcats, would be part of any release project. Any wildcats that formed part of the project would have a full health screen prior to release.

Will the health and welfare of released wildcats be monitored?

If a reintroduction does go ahead, any wildcats released will undergo a full health check and will be vaccinated against a range of appropriate diseases (as determined by Disease Risk Assessment). Post-release monitoring of individuals will be implemented through radio/GPS tracking. Genetic monitoring to ensure integrity of species is retained will be established. Monitoring methods deployed will learn from existing experience elsewhere, for example the Scottish wildcat conservation programme (Saving Wildcats).

Where can I find the project’s reports and studies?

You can find all the reports and studies about the South West Wildcat Project on the Devon Wildlife Trust website. This includes the feasibility report and results from public surveys by The University of Exeter.